The Find

Cotswolds, UK

-

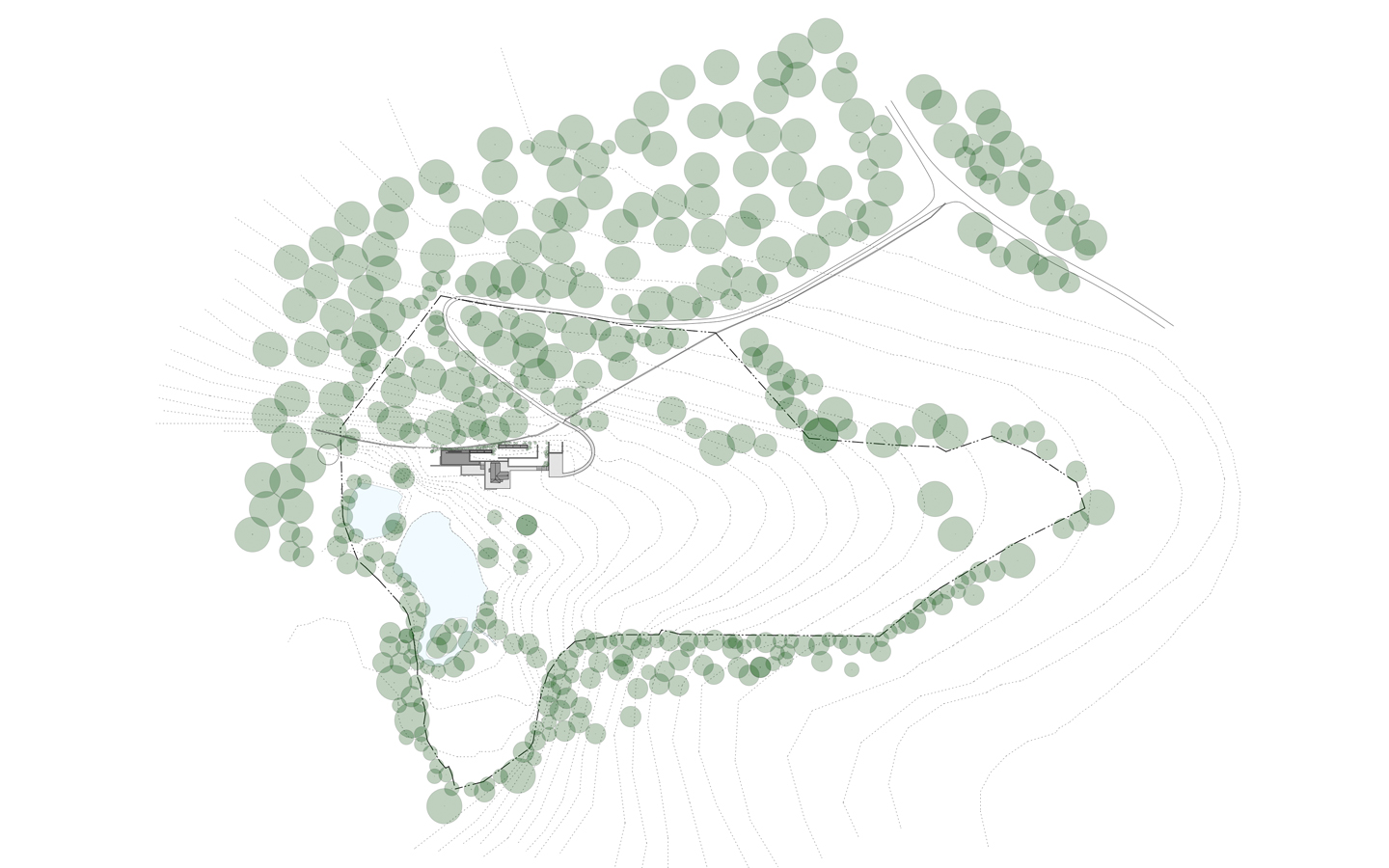

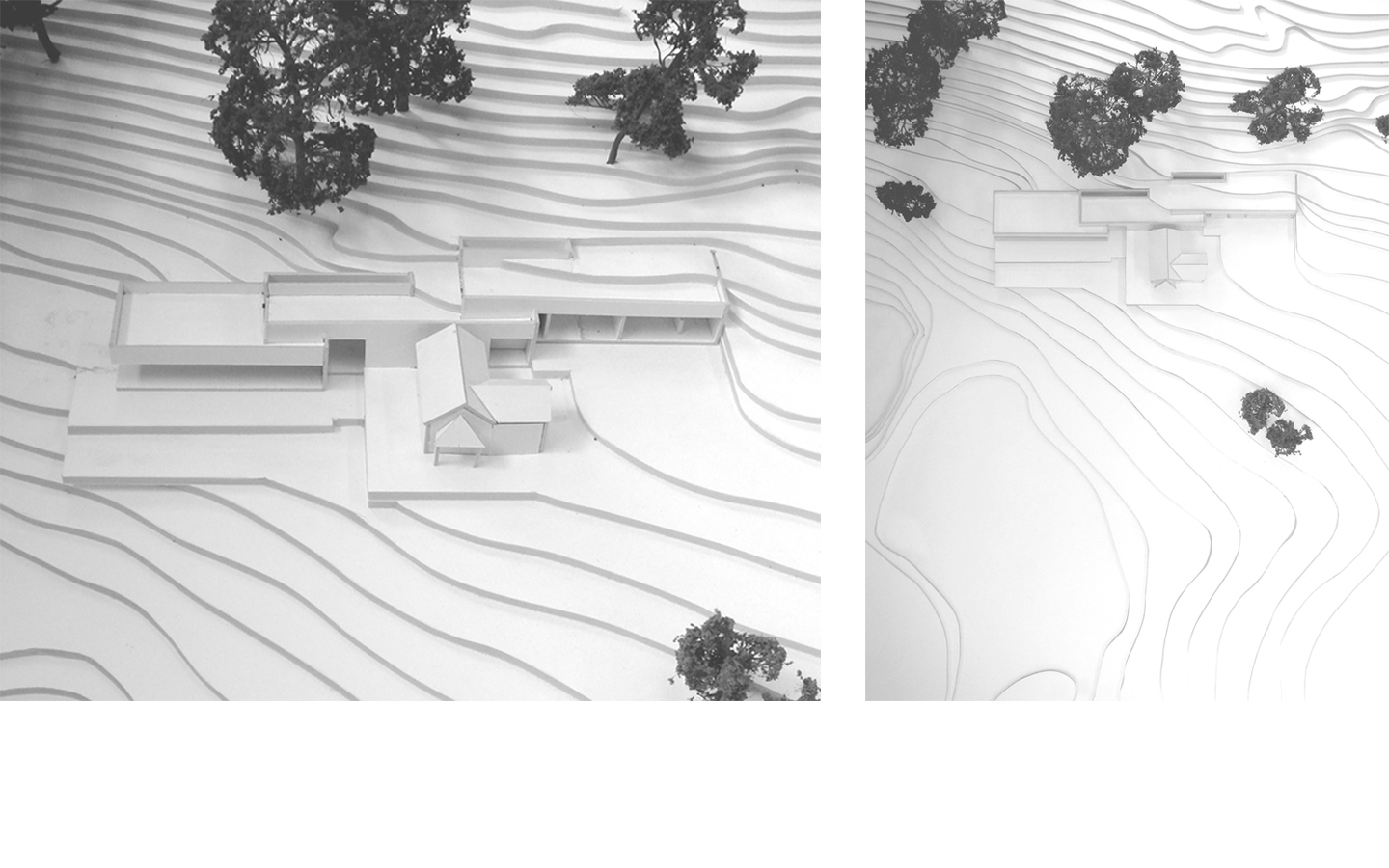

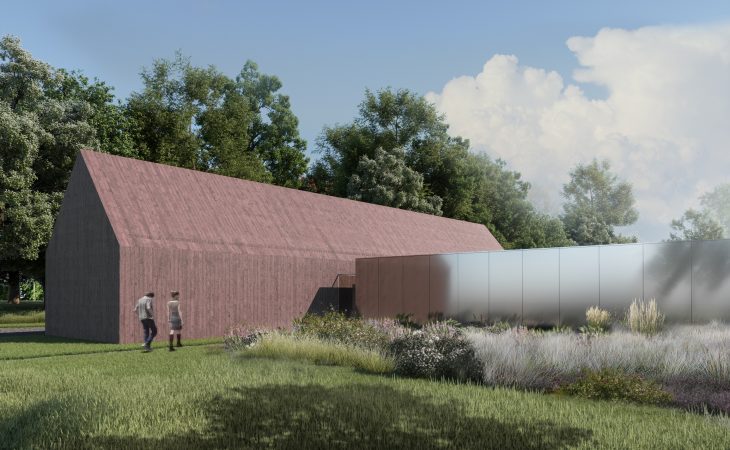

Found Associates, as residential architect, designed this contextual country house consisting of a restored and updated gamekeeper’s cottage and an innovative series of fresh, inter-connected pavilions tucked into the landscape immediately behind it. Together, they form an inviting rural escape set within a secret valley on the edge of the Cotswolds, surrounded by woodland.

The original Grade II listed cottage – dating from the 18th century – remains an integral part of the property, chiefly used by visiting family and friends. The combination of three single-storey pavilions dramatically extends the available living space, with an open plan living area to one side, bedrooms to the other and a linking zone at the centre.

+ -

Residential Projects

-

Val des Portes

Alderney, Channel Islands -

Modern House Architect, Cheshire

Countryside, UK -

Pembroke Walk

Kensington, London -

Barrowgate Road

Chiswick, London -

Ovington Street

Chelsea, London -

Barrowgate Road

Chiswick, London -

Powells Farm

Hampshire, UK -

Residential Interior Design in Harpenden, West Common

Harpenden, Hertfordshire -

Full Refurbishment Notting Hill

Notting Hill, London -

Pezula House

Pezula Estate, South Africa -

Montlaur Farm House

Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France -

Eaton Close

Belgravia, London. -

Chesham House

Belgravia, London -

Lansdowne Road

Notting Hill, London -

Eaton Terrace, Belgravia Architects

Belgravia, London -

Maison Aricobiato Sottano

Corsica, France -

Tree Tops

Derbyshire, UK -

Pencommon

Brecon Beacons, Wales -

Notting Hill Architect Design

Notting Hill, London -

Cathcart Road

Chelsea, London